Life in the Grid. Urban Nature in City Utopias, c. 1600-1750

Life in the Grid. Urban Nature in City Utopias, c. 1600-1750

Mirjam Hähnle

020 7309 2040 m.haehnle@ghil.ac.ukHow should human and non-human beings live together? How should lands and resources be distributed in a model society? In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the place through which utopian answers to such questions were developed and tested was often the city. This project explores urban nature in early modern literary and built ideal cities, interpreting the city as a socio-natural site where human practices and material constellations of humans, artefacts, organisms, and things intermingled (Schatzki 2003).

One of the key assumptions of the project is that literary urban utopias not only formulated radical alternatives to their current socio-political order, but also explored humans’ relationship to nature. In Tommaso Campanella’s Civitas solis(1619) and Johann Valentin Andreae’s Christianopolis (1623), for example, a preservationist approach to the non-human environment seems to emerge, integrated into the cosmic harmony of God, man, and nature. In Thomas More’s Utopia-city of Amaurotum (1516), for example, the equitable distribution of resources was built up as a contrast to the expulsion of the rural population from the English commons.

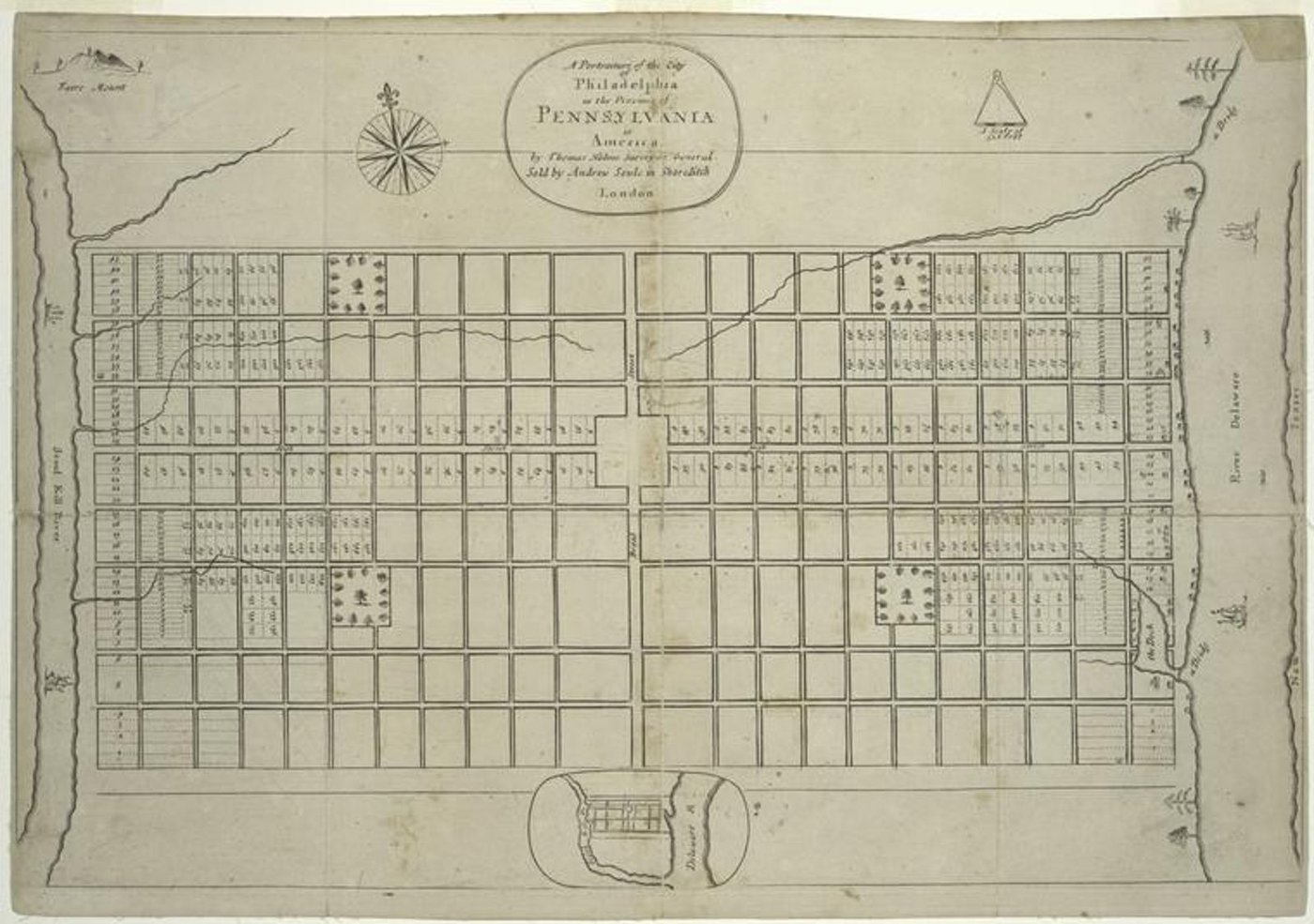

Designs of ideal cities were not confined to literary production, but also executed as urban building practice. The main focus of the project is on two cities that were closely connected to the utopian ideas of Johann Valentin Andreae, Thomas More, and others: Freudenstadt in the Duchy of Württemberg (founded in 1599) and Philadelphia in the newly founded North American colony of Pennsylvania (founded in 1682). Both were built according to predeveloped plans and also to ideal notions of a good social and architectural order. Furthermore, the two cities illustrate decisive transformations of the socio-ecological fabric in the early modern period: In the mining town of Freudenstadt, the duality of religious and resource-economic motivations for the founding of cities can be traced. Philadelphia, on the other hand, testifies to the reshaping of North America in the grid pattern during the course of British colonisation.

The project will focus first on conceptualisations of human-environment relations in the planning phases of the two cities: To what extent did plants and animals find their way into the planning (in the case of Philadelphia, for example, in the form of large parks and the vision of a “green country towne”)? Was the access of all inhabitants to essential resources (as in the literary utopias) an integral part of the planning? A further question is to what extent the city founders’ plans for the socio-ecological design of the city were underpinned by religious concerns. The initial visions of the ideal city will then be examined in relation to everyday life in the first decades after the founding of the cities: The communal pasture and forest areas in both cities, which were in a constant state of transition, will serve as a starting point for observing the planned and unplanned coexistence of humans and non-human beings. Common land also appears as a site of resource conflicts, e.g. over irrigation systems.

The project aims to bring environmental history, infrastructure history and the history of ideas more closely into dialogue with each other. It thus proposes a methodology that connects discursive notions of the ideal city and material practices. The study will show that urban utopias formed a contradictory missing piece in understandings of the relationships between people and their non-human environments in the early modern period. City utopias can be used to trace both the colonial appropriation of people and nature, which was decisively shaped in this era, and the creation of counter-worlds and practices.