The Average Self: A Comparative History of Normality in the 20th Century

The Average Self: A Comparative History of Normality in the 20th Century

Clemens Villinger

020 7309 2038 c.villinger@ghil.ac.ukNormality is something that people only start to think about when it changes. In other words, if you break your arm, or the country that you live in is invaded, the idea of what is normal and what is not changes. However, it is not only individuals but also collectives that negotiate what behaviours, events, or even life courses they consider normal. The social sciences play a central role in these negotiations. By scientifically measuring almost all aspects of human life, researchers produce knowledge about normality that is communicated, reproduced, learned, and passed on in everyday life. Scientific and individual conceptions of normality are therefore not simply given, even if they sometimes seem to be. They are produced, reproduced, and changed over time.

Normality in the “Age of Extremes” (Eric Hobsbawm)

The history of the 20th century is often seen as an “Age of Extremes”. As a result, research tends to focus on states of emergency and crisis. In my project, I reverse this perception and examine the actors who tried to establish normality, order, and stability. I therefore examine how scientists in Germany and Britain produced knowledge about normality in the 20th century. My German-British comparison works on two levels: First, I use a history of knowledge approach to analyse how ideas about ‘normal’ people were produced using scientific methods. Secondly, I use social data from historical and social science studies to analyse whether and why the people studied interpreted themselves, their lives, and their actions as ‘normal’.

‘Normal’ people in Germany and the UK

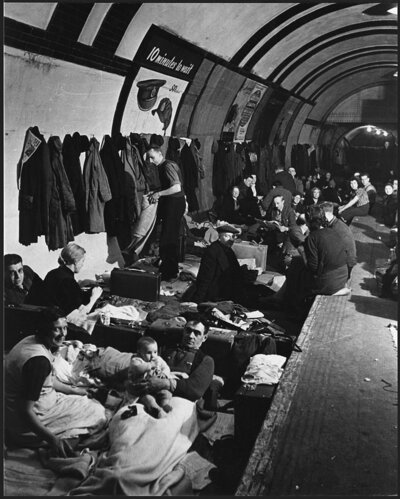

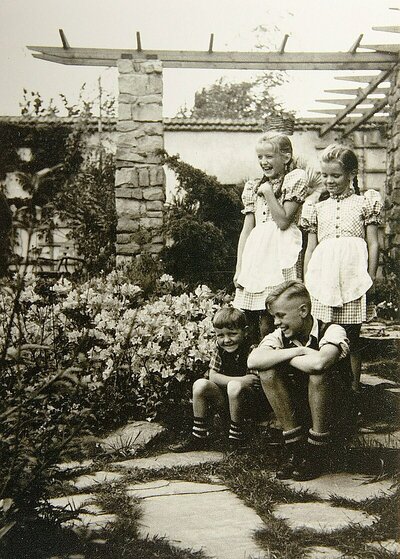

While the scientific methods in Germany and Britain are similar, the experiences of the people I am analysing are different. In particular, the biographies of people who lived in Germany in the first half of the twentieth century are often perceived as ‘not-normal’. This perception is fuelled by the changes in the political system, the two world wars and, not least, the direct and indirect involvement of broad sections of the population in the Holocaust.

This contrasts with the comparatively stable British society, where at least the political system was characterised by continuity during the same period. During the two world wars, and in an explicit differentiation from Germany, Britain was re-conceptualised as a ‘nation of ordinary people’. This British differentiation from Germany as a normal nation of ordinary people makes the comparison productive. My study therefore focuses on research projects that deal with people defined as ‘normal’ or ‘ordinary’ who lived in Britain and Germany between about 1900 and 1990.

Social data from German research projects as historical sources

For the German case study, I want to use data from the Bonn Longitudinal Study of Ageing (BOLSA), collected between 1965 and 1984. In contrast to clinical studies, the subjects were selected on the basis of their demographic normality. The study collected a variety of data: among other things, the interviewees told their life stories along a guideline provided by the scientists. The life stroies were then converted into statistical variables. Therefore, scientifically constructed and individual concepts of normality are intertwined in the BOLSA-Data.

In order to analyse different processes of knowledge production, I also draw on interviews from the oral history project LUSIR (Lebensgeschichte und Sozialkultur im Ruhrgebiet 1930-1960). The interviews, collected in the 1980s, focus on the period from 1933 to 1945 and thus cover a period that was neglected in the BOLSA-study. The interviews provide information on whether the interviewees perceived themselves as having a normal biography and how they narrated it.

Social data from British research projects as historical sources

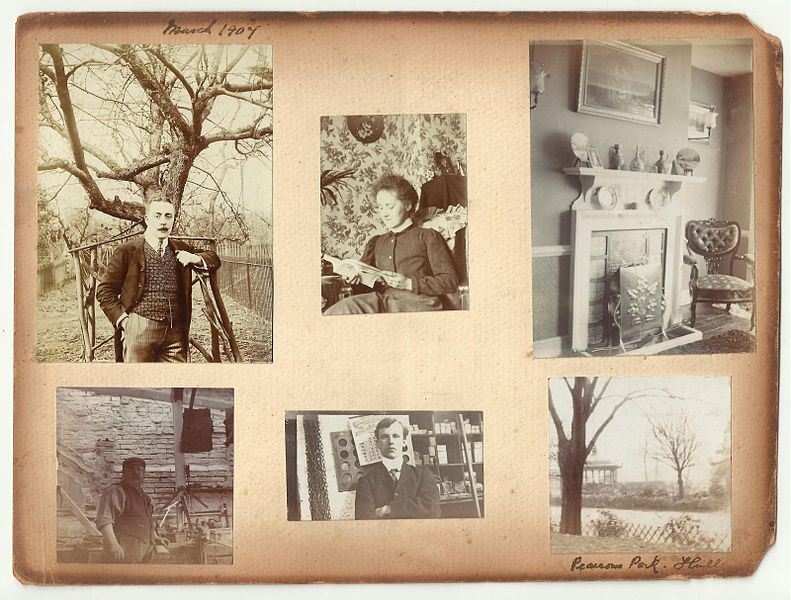

A number of sources are available for the British case study, including ‘The Edwardians: Family Life and Work Experience before 1918’ by Paul Thompson. This project, carried out between 1969 and 1973, used a questionnaire to interview 453 people born between 1873 and 1906. Similar to BOLSA, demographic characteristics rather than medical or social anomalies determined the selection of interviewees.

Based on the social data of the ‘Edwardians’, I intend to use the study ‘Families, Social Mobility and Ageing, an Intergenerational Approach 1900 to 1988’, also conducted by Paul Thompson and Howard Newby between 1985 and 1988. Thompson and Newby justified the focus of their study on average families by pointing to a previous bias in the data towards so-called ‘problem families’.

The Mass Observation archive is a frequently used resource. From the very beginning of the Mass Observation project in the 1930s, categories such as ‘normal’ and ‘ordinary’ were at the centre of the empirical and methodological focus.

Researchers and researched: ‘Doing Normality’ together

There is no lack of sources for my project. The challenge is to create a coherent data base. My research aims to analyse both scientific and individual notions of normality. The social data allows me to make statements about the notions of normality of the researchers, and those of the women and men of different age groups that they studied. The studies in Germany and the UK gave the interviewees the opportunity to talk about themselves and their lives. In telling their stories, respondents were constrained by the research design, which structured the format of the narrative. Nevertheless, the social data offer insights into a shared ‘doing normality’ of researchers and researched in the 20th century.